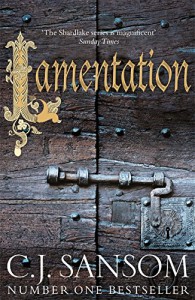

"Lamentation" by C.J. Sansom

Are we born with the innate gift of writing stories? I’m not sure. What I’m pretty sure is that it takes more than being born with a knack for words to write something worth reading. There’s no point for a writer to complain to the gods that she or he does not have the writing skills of Shakespeare, or Dickens, or Heinlein: what a writer needs to do is to the best he/she can with whatever gifts the writer may have, constantly striving with all one’s soul to enhance the mastery of the craft. That very well may be how all those great writers whose natural endowments we all envy had had to achieve their greatness. Probably by constant study, practice, and sweaty hard work. Shakespeare’s first plays may have been better than anyone else’s first plays, but even he didn’t turn out Lear and Othello during his apprentice years.

Mastery of craft is a matter of process, not of a single blinding moment of attainment. The writer goes on working toward it all his life. I’ve always maintained that if one goes about things the right way, one gets better and better all the time, and that means one may get very good indeed. This goes for all spheres of life, being it writing, programming, cooking, inline-skating, scuba-diving, project management, whatever. Heinlein once wrote (in “Time Enough for Love”):

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, programme a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.” (I’ve done most of the things on the list. Unfortunately there was much more manure than sonnets involved…).

I’m not sure about this. This is one of Heinlein’s aphorisms with which I’ve always had the most trouble with. My specialization is in engineering and in later years, management. I used to fit solutions to systems. Other things I’ve done: repair and ride a mountain bicycle, build and fly a rockets, build and race model radio control and slot cars, scuba-diving, inline-skating, kick serious ass in computer-based real time strategy games, create art in a small handful of media, programming, read music, chewing gum, dragging my feet, and twiddle my thumbs. Like any other human being I am capable of carrying out a great number of things, but I specialize in the one thing in which I am outstanding: engineering.

I’m not talking about real proficiency in the functions I’ve listed above. I’ve just stated that I can do these things. To make a difference, I need to stick to the one thing I'm good at to be most effective, and that is engineering. There are also things I am very lousy at: fiction writing, lawn maintenance, handyman at home (eg, picture hanging, woodworking, plumbing, etc). If I need some of these operations performed in and around my house I am likely to call in an expert (my wife). Why do I need to expand my skill set to include specialties I have already shown a lack of talent for? Let me do what I do best, dabble in what I like but lack talent for, and completely ignore that which I suck at (the abovementioned woodworking, plumbing, handyman at home, etc).

I’ve always interpreted Heinlein’s quote as meaning something more along the lines of experience rather than actually performing or mastering all of those tasks, ie, life is meant to be experienced, to be lived in every possible way. Humans should go out and try everything they can in order to feel the joy of living (I’ve taken up mountain bicycle riding, which I hadn’t done in a long time).

Of course, writing is a different thing altogether. There’s much more to writing than mastery of technique. Technique is merely a means to an end, and in this case the end is to convey understanding in the guise of entertainment. The storytelling art evolved as a way of interpreting the world, ie, as a way of creating order out of chaos. To perform the task effectively, the fiction writer must peer into the heart of chaos. This is where C.J. Sansom’s latest book shines.

The plot is deeply satisfying. I didn’t expect the final twist and revelation of who was behind the intrigue against Catherine Parr. All the characters are superb as always. Sansom mix of fact and fiction is quite entrancing. On top of that there is a real feel for 16th century London and Tudor society that allowed me to be “there”. Despite its almost 700 pages, I read it almost in one gulp. What makes this 6th installment so good? It’s not the prose. Sansom’s prose is very workmanlike, but there is something in the setting and the characters that made this one hell of a read. Maybe it’s the de-romanticization of Tudor England?

This is the mark of a wonderful writer, ie, the fact that it’s difficult to pin-point what makes a writer great. As soon as his Shardlake’s books come out, I just grab one, turn off the light, and embark on the journey…Sansom’s books were one my most heartfelt “discoveries” (P.D. James was the culprit). The finding of a new writer that one wants to keep on reading because its imaginative engagement with the world, in this case ancient, was an happening for me. This kind of experience does not happen often, I can tell you.

The Shardlake books retain a marvelously fresh and invigorating quality: They epitomize the hope that Christian faith and charity (at least in individual cases), might yet redeem our inveterate viciousness, and this not due to technique alone. There’s something else at play here…

2

2

2

2